Admiral Zheng He and the Chinese Treasure Fleet

Zheng He (also known as Cheng Ho) was born in what is now Jinning County, Kunming City of Yunnan Province in 1371, the fourth year of the Hongwu reign period (1368-1398) of the Ming Dynasty. He was originally surnamed Ma, and later was known as San Bao (Three Treasures).

Raised a Muslim, Zheng He started to study the teachings of Islam at an early age. Both Zheng He’s father and grandfather had made the pilgrimage to Mecca, and so were quite familiar with distant lands. Under the influence of his father and grandfather, the young Zheng He developed a consuming curiosity about the outside world. Zheng He’s father’s direct character and altruistic nature also made a lasting impression on the boy.

He was only eleven years old, was captured by the Chinese Ming Muslim troops and made a eunuch. He was sent to the court of one the emperor‘s son, Prince Zhu Di. The young eunuch eventually became a trusted adviser and assisted the prince in his insurrection against his nephew the Jianwen Emperor in 1403. For his valor in this war, the eunuch received the name Zheng He. Zheng He served in his court as a Eunuch Grand Director. It was during the Yongle era that Zheng He, with the rank of Chief Envoy carried his first six overseas missions with the Treasure Fleet. Zheng He became a mariner, explorer, diplomat and fleet admiral, who commanded voyages to Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and East Africa, collectively referred to as the Voyages of Zheng He or Voyages of Cheng Ho from 1405 to 1433.

|

Statue from a modern monument to Zheng He at the Stadthuys Museum in Malacca Town, Malaysia. |

In 1425 Yongle’s successor the Hongxi Emperor appointed Zheng He to be Defender of Nanjing. In 1428 the Xuande Emperor ordered him to complete the construction of the magnificent Buddhist nine-storied Da Baoen Temple in Nanjing, and in 1430 appointed him to lead the seventh and final expedition to the “Western Ocean”. It is commonly believed that Zheng He died during the treasure fleet’s last voyage, on the returning trip after the fleet reached Hormuz in 1433.

Expeditions

Between 1405 and 1433, the Ming government sponsored a series of seven naval expeditions. The Yongle emperor designed them to establish a Chinese presence, impose imperial control over trade, impress foreign peoples in the Indian Ocean basin and extend the empire’s tributary system. It has also been claimed, on the basis of later texts, that the voyages also presented an opportunity to seek out Zhu Yunwen (the previous emperor whom the Yongle emperor had usurped and who was rumored to have fled into exile) – possibly the “largest scale manhunt on water in the history of China”.[10]

Zheng He was placed as the admiral in control of the huge fleet and armed forces that undertook these expeditions. Wang Jinghong was appointed his second in command. Zheng He’s first voyage, which departed July 11, 1405, from Suzhou, consisted of a fleet of 317 ships (other sources say 200 ships) holding almost 28,000 crewmen (each ship housing up to 500 men).

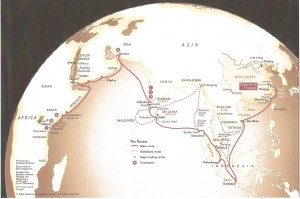

One of a set of maps of Zheng He’s missions, also known as the Mao Kun maps, 1628.

This map is useful to show the extent of the voyages. It is included in the display for you to use with our guests.

Voyages of Zheng He

1405-1433

The ships of Zheng’s armada were as astonishing as its reach. Some accounts claim that the great baochuan, or treasure ships, had nine masts on 400-foot-long (122-meter-long) decks. The largest wooden ships ever built, they dwarfed those of Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama. Hundreds of smaller cargo, war, and supply ships bore tens of thousands of men who brought China to a wider world.

1405-1407

317 ships

27,870 men

In July the fleet left Nanjing with silks, porcelain, and spices for trade. This well-armed floating city defeated pirates in the Strait of Malacca and reached Sumatra, Ceylon, and India.

1407-1409

The fleet returned foreign ambassadors from Sumatra, India, and elsewhere who had traveled to China on the first voyage. The expeditions firmly established the Ming dynasty’s Indian Ocean trade links.

1409-1411

Although notable for the imperial fleet’s only major foreign land battle, the voyage was also marked by Muslim Zheng’s offering of gifts to a Buddhist temple, one of many examples of his ecumenism.

1413-1415

In this voyage’s wake, the first to travel beyond India and cross the Arabian Sea, an estimated 18 states sent tribute and envoys to China, underscoring the Ming emperor’s influence overseas.

1417-1419

Zheng’s Treasure Fleet visited the Arabian Peninsula and, for the first time, Africa. In Aden the sultan presented exotic gifts such as zebras, lions, and ostriches.

1421-1422

Zheng He’s fleet continued the emperor’s version of shuttle diplomacy, returning ambassadors to their native countries after stays of several years, while bringing other foreign dignitaries back to China.

1431-1433

The last voyage, to Africa’s Swahili coast, with a side trip to Mecca, marked the end of China’s golden age of exploration and of Zheng He’s life. He presumably died en route home and was buried at sea.

Source: National Geographic

Zheng He’s fleets visited Arabia, Brunei, East Africa, India, Malay Archipelago and Thailand, dispensing and receiving goods along the way. Zheng He presented gifts of gold, silver, porcelain and silk; in return, China received such novelties as ostriches, zebras, camels, ivory and even a giraffe.

Zheng himself wrote of his travels:

We have traversed more than 100,000 li (50,000 kilometers or 30,000 miles) of immense water spaces and have beheld in the ocean huge waves like mountains rising in the sky, and we have set eyes on barbarian regions far away hidden in a blue transparency of light vapors, while our sails, loftily unfurled like clouds day and night, continued their course [as rapidly] as a star, traversing those savage waves as if we were treading a public thoroughfare… — Tablet erected by Zheng He, Changle, Fujian, 1432. Louise Levathes

It is important to note that while the scale of Zheng He’s fleet was unprecedented (compared to previous voyages from China to the East Indian Ocean), the routes were not. Sea-based trade links had existed between China and the Arabian Peninsula since the Han Dynasty (there being trade with the Roman Empire at that time.) During the Three Kingdoms, the king of Wu sent a diplomatic mission along the coast of Asia, reaching as far as the Eastern Roman Empire. During the Song Dynasty, there was large scale maritime trade from China reaching as far as the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa. In short, Zheng He’s fleet was following long-established, well-mapped routes.

The Ming admiral and his treasure fleet were not engaged in a voyage of exploration, for one simple reason: the Chinese already knew about the ports and countries around the Indian Ocean. Indeed, both Zheng He’s father and grandfather used the honorific hajji, an indication that they had performed their ritual pilgrimage to Mecca, on the Arabian Peninsula. Zheng He was not sailing off into the unknown.

Likewise, the Ming admiral was not sailing out in search of trade. For one thing, in the fifteenth century all the world coveted Chinese silks and porcelain; China had no need to seek out customers – China’s customers came to them. For another, in the Confucian world order, merchants were considered to be among the lowliest members of society. Confucius saw merchants and other middlemen as parasites, profiting on the work of the farmers and artisans who actually produced trade goods. An imperial fleet would not sully itself with such a lowly matter as trade.

If not trade or new horizons, then, what was Zheng He seeking? The seven voyages of the Treasure Fleet were meant to display Chinese might to all the kingdoms and trade ports of the Indian Ocean world, and to bring back exotic toys and novelties for the emperor. In other words, Zheng He’s enormous junks were intended to shock and awe other Asian principalities into offering tribute to the Ming.

Zheng He generally sought to attain his goals through diplomacy, and his large army awed most would-be enemies into submission. But a contemporary reported that Zheng He “walked like a tiger” and did not shrink from violence when he considered it necessary to impress foreign peoples with China’s military might. He ruthlessly suppressed pirates who had long plagued Chinese and southeast Asian waters. For example, he would defeat Chen Zuyi, one of the most feared and respected pirate captains, and return him back to China for execution. He also waged a land war against the Kingdom of Kotte in Ceylon, and he made displays of military force when local officials threatened his fleet in Arabia and East Africa. From his fourth voyage, he brought envoys from thirty states that traveled to China and paid their respects at the Ming court.

So then, why did the Ming halt these voyages in 1433, and either burn the great fleet in its moorings or allow it to rot (depending upon the source)?

There were three principle reasons for this decision. First, the Yongle Emperor who sponsored Zheng He’s first six voyages died in 1424. His son, the Hongle Emperor, was much more conservative and Confucianist in his thought, so he ordered the voyages stopped. (There was one last voyage under Yongle’s grandson, Xuande, in 1430-33.)

In addition to the political motivation, the new emperor had a financial motivation. The treasure fleet voyages cost Ming China enormous amounts of money; since they were not trade excursions, the government recovered little of the cost. The Hongle Emperor inherited a treasury that was much emptier than it might have been, if not for his father’s Indian Ocean adventures. China was self-sufficient; it didn’t need anything from the Indian Ocean world, so why send out these huge fleets?

Finally, during the reigns of the Hongle and Xuande Emperors, Ming China faced a growing threat to its land borders in the west. The Mongols and other Central Asian peoples made increasingly bold raids on western China, forcing the Ming rulers to concentrate their attention and their resources on securing the country’s inland borders.

For all of these reasons, Ming China stopped sending out the magnificent Treasure Fleet. However, it is still tempting to muse on the “what if” questions. What if the Chinese had continued to patrol the Indian Ocean? What if Vasco da Gama’s four little Portuguese caravels had run into a stupendous fleet of more than 250 Chinese junks of various sizes, but all of them larger than the Portuguese flagship? How would world history have been different, if Ming China had ruled the waves in 1497-98?

In 1424, the Yongle Emperor died. His successor, the Hongxi Emperor (reigned 1424–1425), decided to stop the voyages during his short reign. Zheng He made one more voyage during the reign of Hongxi’s son Xuande Emperor (reigned 1426–1435), but after that the voyages of the Chinese treasure ship fleets were ended.

Zheng He returned from his voyages to find a new emperor, whose court was uninterested, even hostile, to the continuation of his naval adventures.

After Zheng He’s voyages, the treasure ships were decommissioned, and sat in harbours until they rotted away. Some suggest that Confucian scholars ordered that many of the treasure ships be burned, although exact information on their fate is not known Chinese craftsmen and officials subsequently lost the knowledge for building such large vessels.

Xuande believed his father’s decision to halt the voyages meritorious, and felt “there would be no need to make a detailed description of his grandfather’s sending Zheng He to the Western Oceans.” Given the lack of respect for the voyages it accounts for the Ming “neglect” of Zheng He in official accounts and the scant records of the voyages available for later historians.

China was split between The Mandarin bureaucrats who generally ran the Empire, and the eunuchs who had control within the Imperial Court. The admiral of the Treasure Fleets was Zheng He (jung huh). Zheng He ended up in the Imperial Court. The eunuchs of the Imperial Court functioned as a separate bureaucracy and the Mandarins were fearful of their power. When the Treasure Fleet expeditions to the Indian Ocean turned out to be successes the Mandarins were so afraid that the power of the eunuchs would be enhanced to the point where they would rival the Mandarins in power that they set to stop the Treasure Fleet expeditions. The Mandarins convinced the Emperor that the Treasure Fleet threaten to contaminate the Empire and must be destroyed.

Less than a century after the distruction of Treasure Fleets the Portuguese appeared in the Indian Ocean in their relative small caravels. Soon the Portuguese gained control over the Indian Ocean and traveled on to China, where they acquired Macau, and on to Japan. How much different would world history have been if the Chinese Treasure Fleets had continued around Africa and one day appeared in the harbors of Western Europe.

While the treasure fleet itself was discontinued, Chinese Maritime activities did continue. Trade was important to them. However, piracy and black market activities also became more prominent.

Protection and the Great Wall

State-sponsored Ming naval efforts declined dramatically after Zheng’s voyages. Starting in the early 15th century, China experienced increasing pressure from resurgent Mongolian tribes from the north. In recognition of this threat and possibly to move closer to his family’s historical geographic power base, in 1421 the emperor Yongle moved the capital north from Nanjing to present-day Beijing. From the new capital he could apply greater imperial supervision to the effort to defend the northern borders. At considerable expense, China launched annual military expeditions from Beijing to weaken the Mongolians. The expenditures necessary for these land campaigns directly competed with the funds necessary to continue naval expeditions.

In 1449 Mongolian cavalry ambushed a land expedition personally led by the emperor Zhengtong less than a day’s march from the walls of the capital. In the Battle of Tumu Fortress the Mongolians wiped out the Chinese army and captured the emperor. This battle had two salient effects. First, it demonstrated the clear threat posed by the northern nomads. Second, the Mongols caused a political crisis in China when they released Zhengtong after his half-brother had proclaimed himself the new Jingtai emperor. Not until 1457 did political stability return when Zhengtong recovered the throne. Upon his return to power China abandoned the strategy of annual land expeditions and instead embarked upon a massive and expensive expansion of the Great Wall of China. In this environment, funding for naval expeditions simply did not happen.

Zheng He died during the treasure fleet’s last voyage. Although he has a tomb in China, it is empty: he was, like many great admirals, buried at sea.[20]

Size of the ships

Early 17th century Chinese woodblock print, thought to represent Zheng He’s ships.

Traditional and popular accounts of Zheng He’s voyages have described a great fleet of gigantic ships, far larger than any other wooden ships in history. Some modern scholars consider these descriptions to be exaggerated.

Scholars disagree about the factual accuracy and correct interpretation of accounts of the treasure ships.

The purported dimensions of these ships at 137 m (450 ft) long and 55 m (180 ft wide are at least twice as long as the largest European ships at the end of the sixteenth century and 40% longer and 65% wider than the largest wooden ships known to have been built at any time anywhere else. These dimensions are disputed with some suggesting they were as short as 61–76 m (200–250 feet) and that they used for river rather than ocean travel.

Chinese recordsassert that Zheng He’s fleet sailed as far as East Africa. According to medieval Chinese sources, Zheng He commanded seven expeditions. The 1405 expedition consisted of 27,800 men and a fleet of 62 treasure ships supported by approximately 190 smaller ships. The fleet included:

- Treasure ships, used by the commander of the fleet and his deputies (nine-masted, about 126.73 metres (416 ft) long and 51.84 metres (170 ft) wide), according to later writers[. This is more or less the size and shape of a football field.

- Equine ships, carrying horses and tribute goods and repair material for the fleet (eight-masted, about 103 m (339 ft) long and 42 m (138 ft) wide).

- Supply ships, containing staple for the crew (seven-masted, about 78 m (257 ft) long and 35 m (115 ft) wide).

- Troop transports , six-masted, about 67 m (220 ft) long and 25 m (83 ft) wide.

- Fuchuan warships, five-masted, about 50 m (165 ft) long.

- Patrol boats, eight-oared, about 37 m (120 ft) long.

- Water tankers, with 1 month’s supply of fresh water.

Six more expeditions took place, from 1407 to 1433, with fleets of comparable size.

If the accounts can be taken as factual, Zheng He’s treasure ships were mammoth ships with nine masts, four decks, and were capable of accommodating more than 500 passengers, as well as a massive amount of cargo. Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta both described multi-masted ships carrying 500 to 1000 passengers in their translated accounts. Niccolò Da Conti, a contemporary of Zheng He, was also an eyewitness of ships in Southeast Asia, claiming to have seen 5 masted junks weighing about 2000 tons. There are even some sources that claim some of the treasure ships might have been as long as 600 feet. On the ships were navigators, explorers, sailors, doctors, workers, and soldiers along with the translator and diarist Gong Zhen.

The largest ships in the fleet, the treasure ships described in Chinese chronicles, would have been several times larger than any wooden ship ever recorded in history, surpassing l’Orient (65 m/213.3 ft long) which was built in the late 18th century. The first ships to attain 126 m (413.4 ft) long were 19th century steamers with iron hulls. Some scholars argue that it is highly unlikely that Zheng He’s ship was 450 feet (137.2 m) in length, some estimating that they were 390–408 feet (118.9–124.4 m) long and 160–166 feet (48.8–50.6 m) wide instead while others put them as small as 200–250 feet (61.0–76.2 m) in length, which would make them smaller than the equine, supply, and troop ships in the fleet.

One explanation for the seemingly inefficient size of these colossal ships was that the largest 44 Zhang treasure ships were merely used by the Emperor and imperial bureaucrats to travel along the Yangtze for court business, including reviewing Zheng He’s expedition fleet. The Yangtze River, with its calmer waters, may have been navigable by these treasure ships. Zheng He, a court eunuch, would not have had the privilege in rank to command the largest of these ships, seaworthy or not. The main ships of Zheng He’s fleet were instead 6 masted 2000-liao ships.

Accounts of medieval travelers

The characteristics of the Chinese ships of the period are described by Western travelers to the East, such as Ibn Battuta and Marco Polo. According to Ibn Battuta, who visited China in 1347:

We stopped in the port of Calicut, in which there were at the time thirteen Chinese vessels, and disembarked. China Sea traveling is done in Chinese ships only, so we shall describe their arrangements. The Chinese vessels are of three kinds; large ships called chunks (junks), middle sized ones called zaws (dhows) and the small ones kakams. The large ships have anything from twelve down to three sails, which are made of bamboo rods plaited into mats. They are never lowered, but turned according to the direction of the wind; at anchor they are left floating in the wind.

Three smaller ones, the “half”, the “third” and the “quarter”, accompany each large vessel. These vessels are built in the towns of Zaytun and Sin-Kalan. The vessel has four decks and contains rooms, cabins, and saloons for merchants; a cabin has chambers and a lavatory, and can be locked by its occupants.

This is the manner after which they are made; two (parallel) walls of very thick wooden (planking) are raised and across the space between them are placed very thick planks (the bulkheads) secured longitudinally and transversely by means of large nails, each three ells in length. When these walls have thus been built the lower deck is fitted in and the ship is launched before the upper works are finished.

– Ibn Battuta

.

Zheng He Timeline:

- June 11, 1360. Zhu Di born, fourth son of future Ming Dynasty founder.

- Jan. 23, 1368. Ming Dynasty founded.

- 1371. Zheng He born to Hui Muslim family in Yunnan, under birth name of Ma He.

- 1380. Zhu Di made Prince of Yan, sent to Beijing.

- 1381. Ming forces conquer Yunnan, kill Ma He’s father and capture boy.

- 1384. Ma He is castrated, sent to serve as a eunuch in Prince of Yan’s household.

- June 30, 1398-July 13, 1402. Reign of Jianwen Emperor.

- August 1399. Prince of Yan rebels against nephew, the Jianwen Emperor.

- 1399. Eunuch Ma He leads Prince of Yan’s forces to victory at Zheng Dike, Beijing.

- July 1402. Prince of Yan captures Nanjing; Jianwen Emperor (probably) dies in palace fire.

- July 17, 1402. Prince of Yan, Zhu Di, becomes Yongle Emperor.

- 1402-1405. Ma He serves as Director of Palace Servants, highest eunuch post.

- 1403. Yongle Emperor orders construction of huge fleet of treasure junks at Nanjing.

- Feb. 11, 1404. Yongle Emperor awards Ma He honorific name “Zheng He.”

- July 11, 1405-Oct. 2 1407. First voyage of Treasure Fleet, led by Admiral Zheng He, to Calicut, India.

- 1407. Treasure Fleet defeats pirate Chen Zuyi at Straights of Malacca; Zheng He takes pirates to Nanjing for execution.

- 1407-1409. Second Voyage of Treasure Fleet, again to Calicut.

- 1409-1410. Yongle Emperor and Ming army battle Mongols.

- 1409-July 6, 1411. Third Voyage of Treasure Fleet to Calicut. Zheng He intervenes in Ceylon succession dispute.

- Dec. 18, 1412-August 12, 1415. Fourth Voyage of the Treasure Fleet to Hormuz. Capture of the pretender Sekandar in Semudera (Sumatra) on return trip.

- 1413-1416. Yongle Emperor’s second campaign against the Mongols.

- May 16, 1417. Yongle Emperor enters new capital city at Beijing, leaves Nanjing forever.

- 1417-August 8, 1419. Fifth Voyage of the Treasure Fleet, to Arabia and East Africa.

- 1421-Sept. 3, 1422. Sixth Voyage of the Treasure Fleet, to East Africa again.

- 1422-1424. Series of campaigns against the Mongols, led by Yongle Emperor.

- Aug. 12, 1424. Yongle Emperor dies of possible stroke while fighting Mongols.

- Sept. 7, 1424. Zhu Gaozhi, eldest son of Yongle Emperor, becomes Hongxi Emperor. Orders stop to Treasure Fleet voyages.

- May 29, 1425. Hongxi Emperor dies. Son Zhu Zhanji becomes Xuande Emperor.

- June 29, 1429. Xuande Emperor orders Zheng He to take one more voyage.

- 1430-1433. Seventh and final Voyage of the Treasure Fleet, to Arabia and East Africa.

- 1433, exact date unknown. Zheng He dies and is buried at sea on the return leg of the final voyage.

- 1433-1436. Zheng He’s companions Ma Huan, Gong Zhen and Fei Xin publish accounts of their travels.

Another source you may want to investigate is the modern study of the Zheng He and the treasure ship by contemporary historians.

- http://www.international.ucla.edu/article.asp?parentid=10387

There is also much discussion about the possibility that China discovered America before Columbus.

- · 1421: The Year China Discovered the World – Gavin Menzies

- http://www.chinesediscoveramerica.com/

- http://history.howstuffworks.com/european-history/chinese-beat-columbus.htm

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/4609074.stm

You can see that this historical period is still of great interest.